Dallas Morse Coors

Legacy Endowment

A Transformational Gift

Dallas Morse Coors embodied the spirit of quiet philanthropy that transforms cultural landscapes. For decades, Dallas Morse Coors—a former member of the Foreign Service and a Bank of America executive—set a noble standard for nurturing the arts in Washington, chief among them the work of Washington Performing Arts and the Washington National Opera.

Coors’s commitment to artistic excellence across genres was profound and personal. He delighted in international orchestras, celebrated vocalists, instrumentalists, and dance companies that graced Washington’s stages. Coors became a pivotal patron of Washington Performing Arts, developing a friendship with President Emeritus Doug Wheeler, and his interest and investment in our organization grew.

After several decades of grantmaking throughout the capital region, the Dallas Morse Coors Foundation made a final endowment distribution to several organizations, per Mr. Coors’s original wishes, in spring 2025. Washington Performing Arts was among the beneficiaries, receiving a generous gift of $8.6 million. The Dallas Morse Coors Legacy Endowment will principally support premier Classical Music and Dance at Washington Performing Arts—including a named performance annually—as well as operational expenses, reinforcing and invigorating our mission and ensuring that Mr. Coors’s legacy of service to the performing arts is long remembered. This endowment gift is a testament to his belief in the transformative power of art and ensures that future generations will experience outstanding performances. At Washington Performing Arts, we are energized and grateful for this visionary generosity.

The Annual

Dallas Morse Coors

Legacy Concert

Coors’s life exemplifies how individual passion can create lasting cultural impact, connecting generations through the universal language of music. In remembering Dallas Morse Coors, we celebrate a visionary who understood that supporting the arts is supporting the human spirit and connection. Each year, Washington Performing Arts will present a Dallas Morse Coors Legacy Concert as part of our annual performance season. The April 14, 2025, concert by renowned pianist Yefim Bronfman is noted as the Inaugural Dallas Morse Coors Legacy Concert.

Inaugural Dallas Morse Coors Legacy Concert

In Memory of Isaac Stern

Yefim Bronfman, piano

Famed for his commanding, powerful technique coupled with exceptional lyricism, Yefim Bronfman performs a solo recital, April 14, 2025.

This performance is presented In Memory of Isaac Stern. Those who hear Yefim Bronfman and Isaac Stern’s multiple recordings or were blessed to see them perform together know how the pair’s collaborative artistry transcended even their individual virtuosity.

Learn More

Dallas Morse Coors

Dallas Morse Coors, born to Herman Frederick and Dorothea Morse Coors on October 26, 1917, was the first grandchild of Adolph Coors, Sr. founder of the Coors Brewery, and was initially named at birth for his grandfather. However, the grandfather’s refusal to support the business venture of his father, Herman, caused his father to turn to his wife’s father. The Morse family was a prominent family in Ithaca, New York, and included noted scientists and engineers including Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph. The Morse grandfather, Virgil D. Morse, agreed to fund the father’s business venture provided his grandson’s name was changed to include important Morse family names Dallas Morse Coors, and it was done. Dallas’s silver baby cup continued to bear his original initials ACIII (his uncle was Adolph Coors, Jr). Dallas was a descendant on his mother’s side of George Mifflin Dallas, a one-time ambassador to the courts of St. James and St. Petersburg and vice-president of the United States under President James K. Polk.

Dallas lived in California as a child. He later attended Putney School, of Putney, Vermont. He then attended Cornell University with which both the Coors and the Morse families had long connections. He was a member of the Quill & Dagger, the senior honor society at that University, and the Kappa Alpha Society, a social fraternity. Dallas reported that some of his best times at the University were singing with its chorus. Dallas graduated from Cornell with a B.A. in 1940. He also later studied at the Institute of Touraine in France and at Georgetown University.

Soon after graduation Dallas joined the Navy for his mandatory duty, and he departed from the Brooklyn Navy Yard by freighter in a 30-day convoy. During WWII, Dallas became a project manager for manufacturers of North American Aviation b51 aircraft. After the war, he joined the US Foreign Service in the State Department where he served as a vice consul in Calcutta, India, and then in Saigon, Vietnam.

In May 1950, Dallas married Princess Sophia Rachmaninoff Wolkonsky from Long Island, New York, a granddaughter of Sergei Rachmaninoff, the important composer and musician. Sophia’s mother was Irina, the first child of Sergei Rachmaninoff. The marriage was in New York City and prominently reported in the New York Times. They divorced in Los Vegas, Nevada, in 1952 and Princess Wolkonsky later married a Wanamaker of Philadelphia.

It is reported that, in 1953, Dallas affiliated with the International Banking Department of the Bank of America. Dallas was concerned in his banking career with issues involving the Middle and Far East. Dallas later worked for the Bank of America with the Foreign Credit Insurance Association.

(FICA) under the direction of the U.S. Department of Commerce and the guidance of the Export-Import Bank offering insurance to U.S. exporters against nonpayment by foreign customers due to commercial and political risks.

After retirement Dallas lived for many years in Washington, D.C., where he developed an active life focusing on performing arts in Washington, D.C. Dallas also acquired an apartment in London as a second home where he spent several months each year. Dallas later sold his homes and moved to a cooperative apartment at the Watergate complex in D.C.

In his final years, Dallas acquired a home and lived in Newport, Rhode Island. Dallas was an active supporter of music in Newport. He arrived at the Newport Music Festival by driving in his midnight blue Rolls Royce with white leather interior up the main drive to the entrance of the grand mansion where the festival was held. Dallas died in Newport, RI, on July 7, 1996.

Before moving to the Watergate complex in Washington and later to Newport, RI, Dallas asked his friends, Patricia Mossel, head of the Washington National Opera, head of the Washington Performing Arts Society Douglas Wheeler, and his then lawyer Doris Blazek-White, and their spouses to a candlelight dinner at his apartment. At that dinner he reflected on his deep love for the performing arts, his affection for the work of the Washington National Opera and the Washington Performing Arts Society and his joy at singing in the student chorus while at Cornell. He announced that he was leaving this estate to a foundation for performing arts in the Washington, D.C.-area and Cornell University. He left the bulk of his estate to that Dallas Morse Coors Foundation for Performing Arts, of Washington, D.C. Between 1992 and 2024 his foundation has given $15,246,900 to 86 performing arts organization in the D.C.-area and Cornell University in annual grants. The Foundation distributed the remaining assets of approximately $18,000,000 in 2025 to Dallas’s three favored organizations as stated in the Foundation’s Trust Agreement.

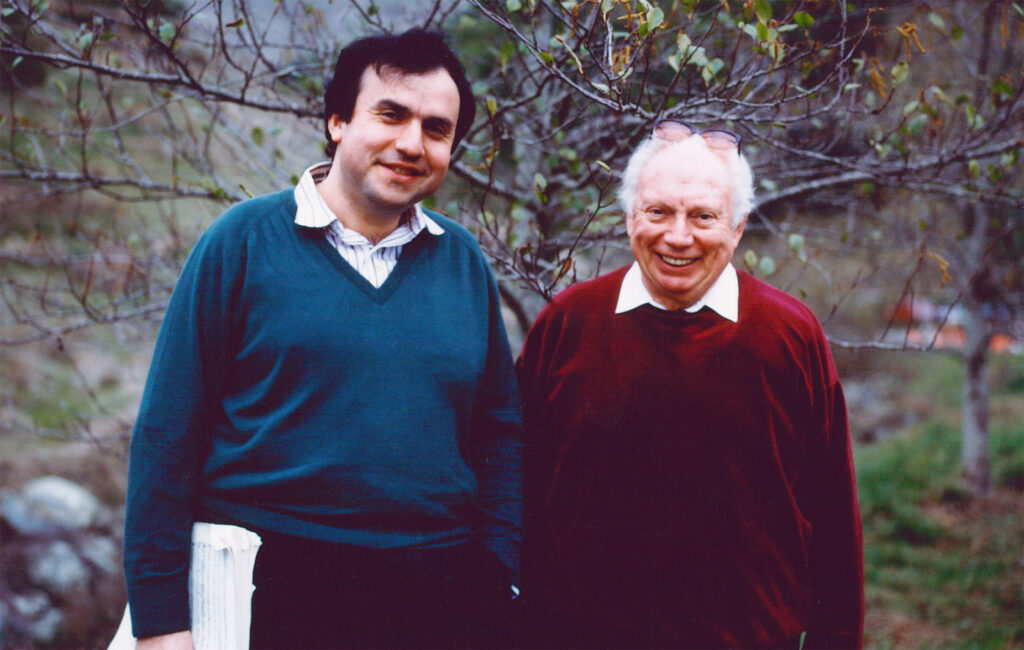

Reflections from Douglas Wheeler, President Emeritus: The Dallas Morse Coors I Knew

I first became aware of Dallas in the mid-1970s. As Manager of Washington Performing Arts Society I put together a week-long engagement in Washington for the Paul Taylor Dance Company which had announced that financial challenges were forcing them to go out of business. Opening night would be a “Dancing for Dear Life” benefit performance to help the company get back on its feet. The invitations went out and the first check through the door was a handsome contribution from Mr. Coors. No one would ever suggest that I was a great fundraiser or I would certainly have pursued Dallas for larger contributions in future years. My training in the field under legendary impresario Patrick Hayes focused more on audience and community building. Mr. Hayes built a successful nonprofit model with the mantra “everybody in, nobody out.” At times it seemed that he spent more time helping other causes than our own. Fifty plus years later, his vision still inspires and his model still endures.

Hayes encouraged me to build my career on community enriching ideas and support would follow. I did invite Dallas to lunch to thank him for his generosity. I discovered a man with a deep interest in classical music and dance, but it gradually became apparent that his interest in the organization extended beyond these passions. As we became friends over the years he encouraged ideas which were helping to define the organization I led as inclusive and at times controversial. Artists who were in the forefront of the culture wars of 30 years ago often showed up on our series. Partnerships with community organizations helping underserved and embattled communities were common, and our board of directors and staff were perhaps the most diverse of all local arts organizations. Dallas listened to my ideas and my occasional worries about programming that might endanger our federal support and counseled me to stay the course. Famously he bought a ticket to a particularly controversial presentation and sat in the front row to show his approval.

His financial support over the years was constant yet modest by today’s standards. I valued his friendship and encouragement the most. I think it surprised and pleased him. When he called one day with an invitation to dinner, to bid farewell, I learned that his health had deteriorated. Upon arrival I found the executive director of the Washington National Opera and his estate attorney were the only others attending. Per his usual gentle grace, he made no requests and no indications of his wishes for his own legacy. It was a fond farewell to the leaders of two organizations he believed in and trusted. Soon after his passing we learned that he had created a foundation to support the performing arts and named the Washington National Opera and Washington Performing Arts Society as the focus of support.

As a friend, and among those most invested in his legacy, I was invited to join Pat Mossel of the Opera and a small group of his friends to help the Trustee of the Foundation create an annual distribution of funds that would support the organizations and art forms that Dallas loved. It was my friend’s quiet sense of community that I shared in those early discussions, a context that resulted in the support of scores of arts organizations and art forms throughout the Washington region. Consequential support to the two institutions Dallas loved the most reinforces and invigorates their missions and insures that Dallas’s legacy of service to the performing arts and his community will carry on well into the future.

Dallas Morse Coors, born to Herman Frederick and Dorothea Morse Coors on October 26, 1917, was the first grandchild of Adolph Coors, Sr. founder of the Coors Brewery, and was initially named at birth for his grandfather. However, the grandfather’s refusal to support the business venture of his father, Herman, caused his father to turn to his wife’s father. The Morse family was a prominent family in Ithaca, New York, and included noted scientists and engineers including Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph. The Morse grandfather, Virgil D. Morse, agreed to fund the father’s business venture provided his grandson’s name was changed to include important Morse family names Dallas Morse Coors, and it was done. Dallas’s silver baby cup continued to bear his original initials ACIII (his uncle was Adolph Coors, Jr). Dallas was a descendant on his mother’s side of George Mifflin Dallas, a one-time ambassador to the courts of St. James and St. Petersburg and vice-president of the United States under President James K. Polk.

Dallas lived in California as a child. He later attended Putney School, of Putney, Vermont. He then attended Cornell University with which both the Coors and the Morse families had long connections. He was a member of the Quill & Dagger, the senior honor society at that University, and the Kappa Alpha Society, a social fraternity. Dallas reported that some of his best times at the University were singing with its chorus. Dallas graduated from Cornell with a B.A. in 1940. He also later studied at the Institute of Touraine in France and at Georgetown University.

Soon after graduation Dallas joined the Navy for his mandatory duty, and he departed from the Brooklyn Navy Yard by freighter in a 30-day convoy. During WWII, Dallas became a project manager for manufacturers of North American Aviation b51 aircraft. After the war, he joined the US Foreign Service in the State Department where he served as a vice consul in Calcutta, India, and then in Saigon, Vietnam.

In May 1950, Dallas married Princess Sophia Rachmaninoff Wolkonsky from Long Island, New York, a granddaughter of Sergei Rachmaninoff, the important composer and musician. Sophia’s mother was Irina, the first child of Sergei Rachmaninoff. The marriage was in New York City and prominently reported in the New York Times. They divorced in Los Vegas, Nevada, in 1952 and Princess Wolkonsky later married a Wanamaker of Philadelphia.

It is reported that, in 1953, Dallas affiliated with the International Banking Department of the Bank of America. Dallas was concerned in his banking career with issues involving the Middle and Far East. Dallas later worked for the Bank of America with the Foreign Credit Insurance Association.

(FICA) under the direction of the U.S. Department of Commerce and the guidance of the Export-Import Bank offering insurance to U.S. exporters against nonpayment by foreign customers due to commercial and political risks.

After retirement Dallas lived for many years in Washington, D.C., where he developed an active life focusing on performing arts in Washington, D.C. Dallas also acquired an apartment in London as a second home where he spent several months each year. Dallas later sold his homes and moved to a cooperative apartment at the Watergate complex in D.C.

In his final years, Dallas acquired a home and lived in Newport, Rhode Island. Dallas was an active supporter of music in Newport. He arrived at the Newport Music Festival by driving in his midnight blue Rolls Royce with white leather interior up the main drive to the entrance of the grand mansion where the festival was held. Dallas died in Newport, RI, on July 7, 1996.

Before moving to the Watergate complex in Washington and later to Newport, RI, Dallas asked his friends, Patricia Mossel, head of the Washington National Opera, head of the Washington Performing Arts Society Douglas Wheeler, and his then lawyer Doris Blazek-White, and their spouses to a candlelight dinner at his apartment. At that dinner he reflected on his deep love for the performing arts, his affection for the work of the Washington National Opera and the Washington Performing Arts Society and his joy at singing in the student chorus while at Cornell. He announced that he was leaving this estate to a foundation for performing arts in the Washington, D.C.-area and Cornell University. He left the bulk of his estate to that Dallas Morse Coors Foundation for Performing Arts, of Washington, D.C. Between 1992 and 2024 his foundation has given $15,246,900 to 86 performing arts organization in the D.C.-area and Cornell University in annual grants. The Foundation distributed the remaining assets of approximately $18,000,000 in 2025 to Dallas’s three favored organizations as stated in the Foundation’s Trust Agreement.

I first became aware of Dallas in the mid-1970s. As Manager of Washington Performing Arts Society I put together a week-long engagement in Washington for the Paul Taylor Dance Company which had announced that financial challenges were forcing them to go out of business. Opening night would be a “Dancing for Dear Life” benefit performance to help the company get back on its feet. The invitations went out and the first check through the door was a handsome contribution from Mr. Coors. No one would ever suggest that I was a great fundraiser or I would certainly have pursued Dallas for larger contributions in future years. My training in the field under legendary impresario Patrick Hayes focused more on audience and community building. Mr. Hayes built a successful nonprofit model with the mantra “everybody in, nobody out.” At times it seemed that he spent more time helping other causes than our own. Fifty plus years later, his vision still inspires and his model still endures.

Hayes encouraged me to build my career on community enriching ideas and support would follow. I did invite Dallas to lunch to thank him for his generosity. I discovered a man with a deep interest in classical music and dance, but it gradually became apparent that his interest in the organization extended beyond these passions. As we became friends over the years he encouraged ideas which were helping to define the organization I led as inclusive and at times controversial. Artists who were in the forefront of the culture wars of 30 years ago often showed up on our series. Partnerships with community organizations helping underserved and embattled communities were common, and our board of directors and staff were perhaps the most diverse of all local arts organizations. Dallas listened to my ideas and my occasional worries about programming that might endanger our federal support and counseled me to stay the course. Famously he bought a ticket to a particularly controversial presentation and sat in the front row to show his approval.

His financial support over the years was constant yet modest by today’s standards. I valued his friendship and encouragement the most. I think it surprised and pleased him. When he called one day with an invitation to dinner, to bid farewell, I learned that his health had deteriorated. Upon arrival I found the executive director of the Washington National Opera and his estate attorney were the only others attending. Per his usual gentle grace, he made no requests and no indications of his wishes for his own legacy. It was a fond farewell to the leaders of two organizations he believed in and trusted. Soon after his passing we learned that he had created a foundation to support the performing arts and named the Washington National Opera and Washington Performing Arts Society as the focus of support.

As a friend, and among those most invested in his legacy, I was invited to join Pat Mossel of the Opera and a small group of his friends to help the Trustee of the Foundation create an annual distribution of funds that would support the organizations and art forms that Dallas loved. It was my friend’s quiet sense of community that I shared in those early discussions, a context that resulted in the support of scores of arts organizations and art forms throughout the Washington region. Consequential support to the two institutions Dallas loved the most reinforces and invigorates their missions and insures that Dallas’s legacy of service to the performing arts and his community will carry on well into the future.